Alexandra Robinson, “After Cōātlīcue,” 2023, cyanotype on muslin, grosgrain ribbon, fringe, gold tinsel, brass frame, 6 feet tall. Photo: Renee Lai

I’ve seen Alex Robinson’s work around Austin, most recently at her Women & Their Work solo show in 2022. I was struck by how many interests we have in common — in our practices we both grapple with nationhood and what it means to be American. Robinson’s show at Artpace San Antonio continued to include flag and fabric elements that expanded on prior themes, but her use of audio and video work in the installation was new to me. I was also particularly taken by her series of prints and the play on the word “land” throughout the show. I recently had the opportunity to talk with Robinson; the following interview is a lightly edited and condensed version of our conversation.

Renee Lai (RL): There seems to be a strong relationship between inside and outside in this Artpace show. The rocks come from the outside, and they’re arranged inside in these spiral paths that made me think about labyrinths. They also remind me of New England fences, the way farmers used to pile their stones to demarcate borders of land. The main figurative element faces towards the outside to invite the viewer to look through the window to another work of yours, the flag. How do you think about pulling inside/outside together, and how did you get all of the rock here?

Alex Robinson (AR): I’m a transplant to Texas. The place I lived through high school was in a more rural area outside of Kansas City and was associated with a military base. I’ve been doing some variation of a drive there, whether it is from the east coast, or Texas, or wherever, since I was 15 years old, and the drive became symbolic of movement. The road to get there is not new. I-35 isn’t directly aligned with the Chisholm trail, but it follows a longstanding migration path of people moving to Kansas for reservation, and it also makes me think about cattle drives.

In the region there is a prevalence of dry stacked stone walls. They’re everywhere now, but weren’t always, because laws about partitioning your land after purchase didn’t come about until the late 1860s. The rocks in the gallery are Texas limestone. The cleaner looking ones have been tumbled, but are from underground. The dirty ones are fieldstone, meaning stones that were on the surface and have been affected by weather. I thought it was important to think about what is both underneath and on the surface. We are on the edge of grassland in Central Texas, but there aren’t a lot of examples of native prairies here. The grass root system is one or two times longer than the grasses you see here now. I was listening to LBJ’s biographies and the first book, The Path to Power, by Robert Caro, talks about what Central Texas used to look like. When families were first coming, there were lush grasslands and they saw it as fertile land. Once they tilled it up, the soil washed away and they were left with rock. This acts as a metaphor for the way people in this region have been treated over time.

RL: I found the video work mounted on the ceiling to be very surprising. It is slightly hidden by the architecture, so it emerges only as you start to walk through the space. In the video, scenes of grassland rushing by, blurred from motion, are interspersed with more still shots of grass waving in the breeze. It felt disorienting as I stood there and craned my head to look up. Can you talk about how and where you filmed it, and your decision to mount it on the ceiling?

AR: I have been filming grass since 2019. The footage is from Kansas and Texas. When I was initially conceiving everything I thought it was going to be a projection. I knew I wanted to do something with the grass, but I also wanted it to feel like an abstraction, like it was going too quickly for you to catch what it was. Grass is much bigger than we know, and it can’t be a single crop because it loses diversity. The lack of diversity creates problems. So the idea of the meadow or the plains echos similar ideas in my mind about people and the land. I was thinking about it in parallel to the construct of the U.S. and personhood and nationhood.

In the studio I kept placing [the video] on the floor on my phone, but it didn’t work on a large scale. Everything else in the room is looking down, so I wanted to make you look up, to have it be disorienting. It is awkward to tip your head up, that this thing is moving so there is no place to ground yourself. Hiding it in the architecture reinforced having the viewer walk through the rocks because it is not something you see immediately upon arrival.

Alexandra Robinson, “This land is my land this land is your land,” 2023, field and chopped limestone of various sizes, cotton, American and Mexican flags, and grosgrain ribbon, dimensions variable. Photo: Renee Lai

RL: There are little surprises hidden throughout your show — the scraps of fabric tucked into the rocks, the flag installed outside of the gallery space, the video work in the ceiling, the way the cape faces its back to you as you walk in, and the way the blue paint on the gallery walls slowly fades to white — it took me a while to notice that! How do you think about moving the viewer physically through your installation?

AR: It started with the cape form. I felt like I couldn’t show it all immediately, so it had to face away when you enter. That set the tone for everything else. I wasn’t sure how many people would find the things embedded in the rocks. I was thinking about the things we discard, bury, or get left as things change or move. The painted wall is fascinating to me because you’re not the only person who didn’t notice it at the beginning. I wanted it to feel like we’re above, looking down, navigating through the installation.

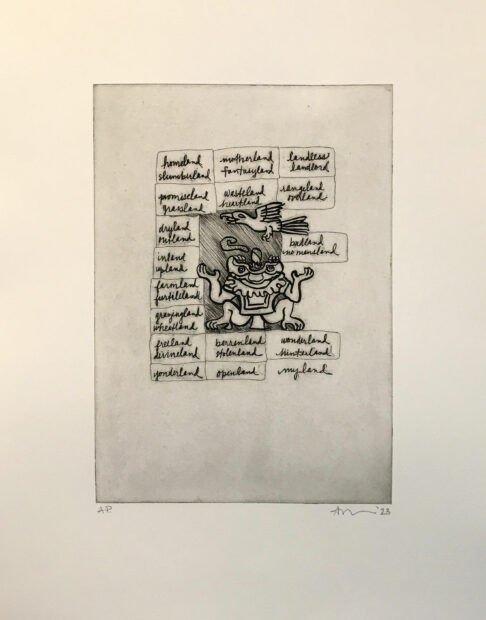

Alexandra Robinson,” Homeland #2 (Tlaltecuhtli),” 2023, photopolymer gravure on BFK, 11.5×8.25 inches. Photo: Renee Lai.

RL: I am really interested in the play of words, even in the title of the show and in the three prints included. How did you first begin to be interested in associations with the word “land,” and how did you begin to play with text in your work?

AR: A lot of the research that I use is based on government documents. Usually they are documents that represent violence in some way. For this show, I used the Homestead Act. When I think about the language of progress or ownership, this is the type of language that pops up. I also used the National Archives. I spent a bunch of time looking for early recordings of Mexican ballads — they’re really charged in language. There’s a band called el Tigre de Norte that plays Norteño style music. In their songs, they talk about the plight of the early migrants and how the brownness of their skin contrasts with the whiteness of the settlers. I wanted to riff off the words of the popular song “This Land is Your Land” by Woody Guhtire. I started to look up words that included the word land so that’s how the pile of words came about.

Alexandra Robinson, “After Cōātlīcue,” 2023, cyanotype on muslin, grosgrain ribbone, fringe, gold tinsel, brass frame, 6 feet tall. Photo: Renee Lai

RL: How did your interest in fabric begin?

AR: In 2018 or 2019, I did a middle school workshop with Jimmy Luu, a graphic design professor at St. Edward’s University, where we made flags. When I did the residency at the Tallgrass prairie in 2019, I took a bunch of material and I made cyanotype flags. I wanted to figure out how to signal messages in the landscape. In 2016 I was making Morse code drawings and I was using information systems to make messages. I thought about flag semaphores, so I started to play with making flags with things that I claim — I am a mother, I am a daughter, I am Mexican, I am Jewish, etc. I started researching flags…prior to that in 2016 or 17, I did a project with students at St. Edward’s that was part of an exhibition at the Bullock Texas State History Museum. The students made panels that hung in a circular formation and they had to use certain materials. I had to buy sewing machines and teach them how to sew, and in the process I had to re-learn how to do it. So these bits and pieces of language and meaning and traveling and fabric slowly connected…now I love the fabric. Drawing on the fabric, preparing the fabric — it is very immediate. I like that.

Alex Robinson’s show at Artpace San Antonio, this land is my land \ this land is your land, is on view through January 7, 2024. You can learn more about the show here.